Must the Clanwilliam cedar get a new name?

This lovely specimen of the Clanwilliam cedar is growing in the central Cederberg – the species survives today in only about 250 square kilometres of the Western Cape’s Cederberg.

Follow the twists and turns of a botanical detective story after local botanists were shocked by the Clanwilliam cedar losing its proudly SA botanical name more than a decade ago. Now they are celebrating the elegant casework of PETER LINDER and JOHN MANNING, who have succeeded in restoring it to the world

PHOTOS BY PETER LINDER

Most South African plant lovers have heard of the iconic Clanwilliam cedar but relatively few might actually have seen it. It is now classified as critically endangered on the Red List of South African Plants and survives in only about 250 square kilometres in the Cederberg, the mountain range from which its botanical name Widdringtonia cedarbergensis is derived.

MEET THE RELATIVES

The Clanwilliam cedar is the largest of the three cedar species that occur naturally in South Africa. It is endemic to a small part of the Cederberg Wilderness Area where a few remain.

Six hundred or more kilometres further east grows a very similar relative, the Willowmore cedar W. schwarzii, almost endemic to the Kouga and Baviaanskloof mountains, although with small populations also in the Grootrivierberge. This species differs from the Clanwilliam cedar in having smaller, distinctly winged seeds.

Increasing fires in their habitat mean that both the Clanwilliam and the Willowmore cedars face uncertain futures.

The Clanwilliam cedar and the Willowmore cedar (seen here) are both endemic to southern Africa. Photo by Douglas Euston-Brown

FAR AND WIDE

In contrast to these two restricted species, the smaller, multi-stemmed resprouting mountain cypress W. nodiflora is much more common and widespread. Its range extends about 2 500 kilometres from the mountains above Tulbagh north east to Mount Mulanje in Malawi.

The fourth and final member of the Widdringtonia is the Mulanje cedar W. whytei, another tall reseeding species but endemic only to Mount Mulanje. By 2004, only 845 hectares of cedar were left on the mountain – and even there about a third of the trees were dead.

CEDERBERG IDENTITY CRISIS

Of the four, the future survival of the Clanwilliam cedar is the most tenuous – and until we recently delved into the botanical archives, even its resounding botanical name was under threat, with some prominent taxonomists having already changed it. . .

Using names correctly and consistently is a prerequisite for accumulating and accessing information about anything. Any name change is disruptive but in formal biological naming (nomenclature), this process is never arbitrary. It is done only after careful consideration of the facts, and follows strict protocols that have developed over the centuries as our understanding of plant life and taxonomy has deepened.

Modern technology has also helped us cross-reference conclusions in plant research and naming, both across the world and back through the centuries. Inevitably, anomalies appear from time to time and some can turn into fascinating botanical puzzles.

FOLLOWING LINNAEUS

The first scientist to describe specimens of the Clanwilliam cedar was the Vienna-based botanist Stephan Endlicher (1804-1849) for his 1847 Synopsis Coniferum. He adopted the name Cupressus juniperoides, which had been published more than eighty years earlier in 1763 by the famous Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778).

The type specimen for C. juniperoides is in the Linnean herbarium in London – but it is actually a specimen of the related mountain cypress. Endlicher can be forgiven for not realising this at the time as the two species look very alike if you do not have an intimate knowledge of their cones, growth form and size. The upshot of this confusion was that the Clanwilliam cedar was left without a valid botanical name.

Seeds of the Clanwilliam cedar – frequency and timing of fires affects whether they will successfully generate seedlings.

WHOSE NAME IS IT ANYWAY?

To remedy this, in 1966 Judith Marsh (b.1941) of the SA National Herbarium provided the species with the name W. cedarbergensis. This botanical name was used for the Clanwilliam cedar until 2011 when the Plants of the World Online website substituted the name W. wallichii. But was this decision justified?

There is always plenty of room for discussion and debate among plant taxonomists. Many plant names may surface in historical accounts and collectors’ notebooks, for example – but not all are scientifically accepted.

A critical fact to bear in mind is that the identity of any plant name is determined solely by a particular specimen which has been designated the type specimen – ideally representing the key physical features of the species. In other words, the plant’s identity is fixed by this specimen and does not change according to the way that the name has come to be used or applied by anybody.

REWINDING THE PLOT

In surveying conifer species for his book, Endlicher had looked at some of the first recorded specimens of Clanwilliam cedar to reach the hubs of botany at the time in Europe. Professional plant collector Johann Franz Drège (1794-1881) had collected specimens of the tree on both 24 November 1828 and again on 4 January 1831.

Drège collected his specimens from between Boskloof and Heuningvlei – which we believe to be from Krakadouw – in the northern Cederberg.

LOST NAMES

Drège sold and distributed his specimens to several European herbaria under the names Callitris arborea or C. stricta, although neither of these names was ever validly published in the scientific literature. Callitris is an Australian genus that is very similar to Widdringtonia and indeed closely related to it. However, Callitris has female cones with six scales in two whorls, whereas the African Widdringtonia has female cones with just four scales.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the generic classification of the cypress family (Cupressaceae) was still unresolved. This was reflected in how southern African species were treated scientifically, first as Cupressus in 1763, then Callitris and then Pachylepis before finally settling in Widdringtonia in 1842.

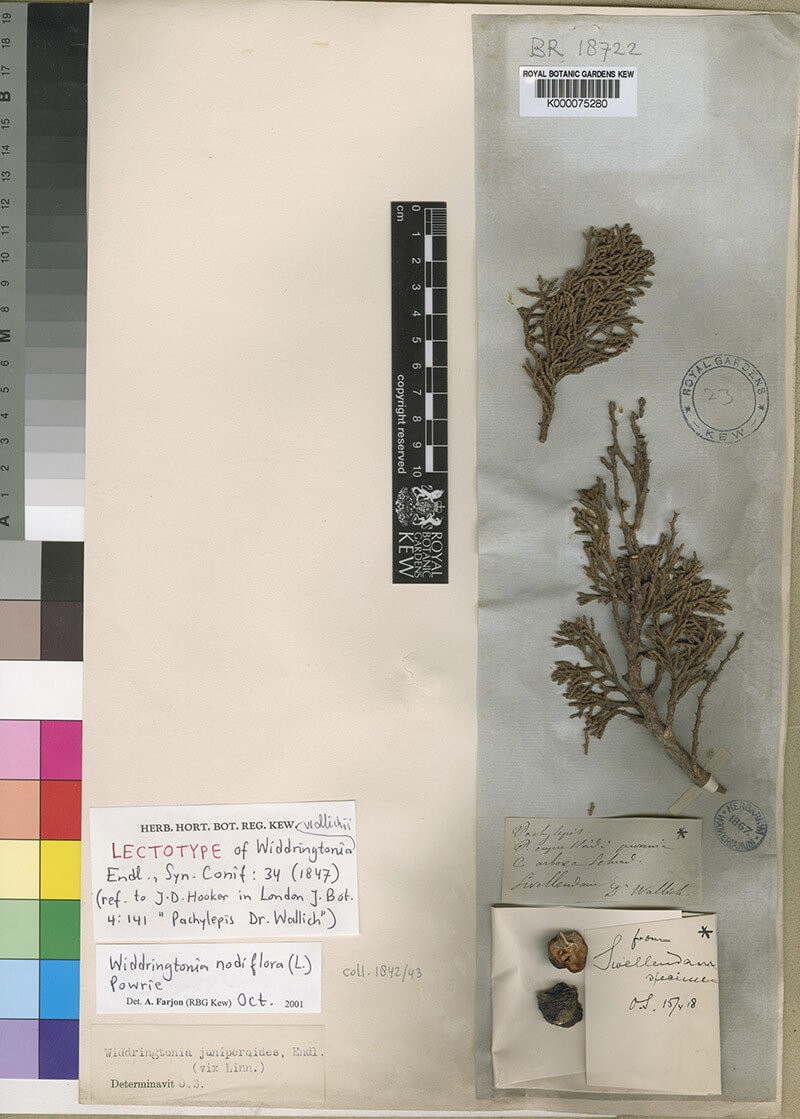

A piece of history – this specimen of the mountain cypress was collected by Nataniel Wallich in 1843 and is now part of the herbarium collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London. Photo © Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

BACK IN THE CEDERBERG

About a decade after Drège collected the Clanwilliam cedar in the Cederberg, he was followed there by Danish botanist Dr Nataniel Wallich (1785-1854). Wallich, who was then superintendent of the Calcutta (now Kolkata) botanic gardens, visited the Cape at the beginning of 1843.

During this trip, he travelled with Thomas Maclear (1794-1879) to the Cederberg, where he made his collection of the Clanwilliam cedar, and later to Swellendam, where he collected the mountain cypress.

The Clanwilliam cedar specimen is now in the Natural History Museum in London and the Swellendam one of the mountain cypress is in the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Irish-born Maclear was a renowned astronomer who laid the foundation for the trigonometrical survey of South Africa and whose beacon marks the highest point on Table Mountain.

THE WALLICH CURVE BALL

Two years later, J.D. Hooker (1817-1911), then director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, mentioned Wallich’s specimen in the Kew collection in an article in the London Journal of Botany: ‘Dr. Wallich sent another Pachylepis from South Africa certainly distinct from P. cupressoides, which may however be the C. stricta.’

It was soon after this, in his 1847 account of Cupressaceae, that Endlicher included a brief reference to the Wallich specimen of the mountain cypress that Hooker had mentioned. Under the heading ‘Species inquirendae’ (species to be investigated), Endlicher proposed naming it W. wallichii in honour of Wallich.

Endlicher seems not to have seen the specimen himself but based his entry solely on Hooker’s comment. He certainly did not provide a description of it to accompany the name – which is required to ensure the name is botanically valid by combining the name and the identifying features. At this stage, therefore, the name W. wallichii was an invalid name so could not be used.

MOVING ON

Almost a century later, in 1933, the influential Austrian botanist Otto Stapf (1857-1933), working at Kew, published his account of Cupressaceae for the Flora Capensis. Stapf followed Endlicher, who had moved all the African cedars to Widdringtonia and applied the Linnean species epithet juniperoides to the Clanwilliam cedar, making its new scientific name W. juniperoides.

Stapf had been able to study the Wallich mountain cypress specimen at Kew and the Clanwilliam cedar at London’s Natural History Museum. He concluded that both matched Drège’s earlier specimens from the Cederberg and so also belonged to the Clanwilliam cedar. In fact, he believed that the locality of Swellendam noted on the Kew specimen was incorrect and should have been Clanwilliam – this view has not been supported by later botanists. Stapf considered the two specimens as coming from the same species and therefore treated the later name W. wallichii as a synonym of W. juniperoides. His decision would illustrate once again the difference between the identity intended by a plant name – as determined by the type specimen – and the way users apply the name.

RESURRECTING WALLICHII

However, Stapf cited the description of Widdringtonia wallichii in the 1867 second edition of Traité général des Conifères by French horticulturist Élie-Abel Carrière (1818-1896), a leading authority on conifers. Although Carrière’s book is more a guide to cultivated conifers than a taxonomic treatment, he had provided a description under the name Widdringtonia wallichii.

This fulfilled the requirements for rendering the name botanically valid but, under the nomenclatural practice of the time, W. juniperoides was still the oldest valid name so this is what Stapf used.

The female cones of the Clanwilliam cedar turn grey when they are ripe.

Later authors either missed or ignored this description. It was not until the 21st century, when a Belgian taxonomist working at Kew, Rafaël Govaerts (b.1968), picked up the oversight. In 2011, he resurrected Stapf’s use of the name W. wallichii as the earliest valid name for the Clanwilliam cedar on the authoritative website Plants of the World Online.

DEPENDING ON EVIDENCE

On the face of it, Carrière’s valid 1867 publication of the name complete with the species description meant that it long predated Judith Marsh’s well-intentioned 1966 attempt to fill what then seemed to be a naming gap. But there was a twist in the tale . . . What actually was Carrière’s Widdringtonia wallichii?

According to the rules governing the scientific naming of plants, the identity of W. wallichii must be determined solely by the material that Carrière cited when he published the name. It is not regulated by the Wallich specimen that Hooker saw, for instance, since Carrière did not cite this. In fact, amazingly, Carrière listed no specimens at all.

His description is very general – so general that it is impossible to be sure that the description even refers to a Widdringtonia! He does not mention any cones so cannot have seen either the Drège or the Wallich collections, both of which have cones.

PARISIAN MYSTERY

The tree that Carrière described was up to 12 metres tall – Clanwilliam cedars become reproductive at about two metres. Mention of the height suggests that he was describing a tree in cultivation since none of the early collections of W. cedarbegensis give the height of the plants.

Although Carrière also noted that the species was ‘Introduit vers 1844’ (introduced around 1844), he could have derived this date from Hooker’s paper. Similarly, the supposed source of Carrière’s plant as ‘Habite l’Afrique australe’ (lives in southern Africa) could have been derived directly from Hooker’s notes.

Intriguingly, Carrère then goes on to note that his species ‘Gèle a Paris’ (freezes in Paris). As well as suggesting that the tree was not hardy in Paris, this also indicates that it was a cultivated tree. This nugget seems likely to have been derived from his own observations.

There is a herbarium specimen of mountain cypress (W. nodiflora) in the Paris herbarium, collected in 1868, from a tree cultivated in a local garden. Although we cannot trace the garden itself, this does indicate that W. nodiflora was in cultivation in France at the time.

The mountain cypress is found in high mountain areas from the Western Cape through the Drakensberg to Malawi. It is known as a resprouter, often coppicing to recover from fire.

CHAIN OF EVIDENCE

In summary, without direct reference to a specimen, the scientific chain of evidence breaks down and we really cannot tell what plant Carrière described. It could be the mountain cypress or possibly the similar Clanwilliam cedar – or even something else entirely. The name W. wallichii was thus at this stage a nomenclatural time-bomb!

In a case like this, where there is no original material to fix the usage of a name, botanists are empowered to select a new type specimen that will serve to fix the use of the name. We have consequently selected a fine collection of the mountain cypress from the Langeberg near Swellendam to serve this critical function. This collection is represented in our two largest local herbaria, the Compton Herbarium in Cape Town and the National Herbarium in Pretoria. The results of our research will soon be published in the local scientific journal Bothalia: African Biodiversity and Conservation.

As a result:

- The name Widdringtonia wallichii becomes a later synonym of W. nodiflora

- This leaves W. cedarbergensis as the valid name of the Clanwilliam cedar

It is certainly a relief to all of us that the Clanwilliam cedar will thus retain the very apt botanical name that Judith Marsh coined for it and under which it has been known for well over half a century.

Peter Linder (

John Manning (

The Willowmore cedar is gnarled and slow growing but can reach up to 20 metres high. Like the Clanwilliam cedar, it is particularly vulnerable to fire. Photo by Douglas Euston-Brown

Showing the way

In the botanical world, the provision and application of plant names is regulated by the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants. This comprehensive code is managed and regularly updated through the International Association of Plant Taxonomists and is available here.

The ICN’s primary aims are clearly summarised in 14 points in the code’s preamble. Three of the most crucial points are:

Point 1: Biology requires a precise and simple system of nomenclature that is used in all countries.

Point 5: The object of the rules is to put the nomenclature of the past into order and to provide for that of the future; names contrary to a rule cannot be maintained.

Point 12: The only proper reasons for changing a name are either a more profound knowledge of the facts resulting from adequate taxonomic study or the necessity of giving up a name that is contrary to the rules.